How we evaluate D2C companies

Recently, the viability VC investments in direct-to-consumer (D2C) companies has been called into question. We unpack the D2C business model and share our evaluation criteria for investments.

Apple. Tesla. LVMH. Nike. Coca Cola.

These are some of the most iconic, valuable, and significant companies in the world - and they are all in the business of designing, manufacturing, and selling products to consumers.

In the last decade, a cohort of companies took advantage of platform and behaviour shifts, such as the widespread adoption of eCommerce and availability of social media advertising, to rapidly scale companies that marketed and distributed products directly to consumers. These companies bypassed traditional merchants (such as supermarkets and department stores) - in fact, many bypassed the brick and mortar retail experience all together.

Some early examples of these ‘direct-to-consumer’ (D2C) companies included Warby Parker, Casper, Dollar Shave Club, Glossier, Away Luggage, and Allbirds.

In this article, we:

Unpack the conditions that allowed the first cohort of D2C companies to scale rapidly

Analyse how their advantage was eventually eroded

Outline what is table stakes for operating a successful D2C business today

Discuss what a ‘venture backable’ D2C company looks like.

Why were D2C companies initially so successful?

Monopolistic incumbents ripe for disruption

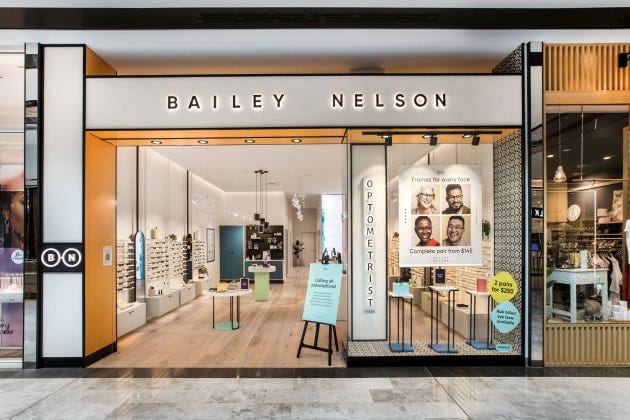

Warby Parker was founded in 2010 by four friends who had met at Wharton. They happened upon a key insight about the eyewear industry: it was dominated by a monopolistic global player called Luxottica - which is better known by the brands it owns and licenses: from Ray-Ban and Oakley to Chanel and Prada. It supplies differently branded, but functionally identical products to retailers like OPSM and Sunglass Hut. Because Luxottica controls both manufacturing and distribution, customers end up with high prices for limited options.

Warby saw an opportunity to disrupt this industry by creating a vertically integrated business model that cut out the middleman and offered high quality, stylish eyewear at an affordable price point. By designing and manufacturing their own frames and selling directly to consumers online, Warby was able to offer glasses at a fraction of the cost of traditional retailers.

Customers’ growing comfort with buying online

Founded in 2014, Mattress-in-a-box maker Casper is an example of a company that built their customers’ comfort in buying a product without experiencing it in a physical store.

Casper offered customers a 100-night trial period during which they could try out the mattress. If a customer decided they didn't want to keep the mattress, Casper would pick it up and donate it to a local charity. This policy differentiated Casper’s customer proposition, but also delivered significant cost savings - because customers felt comfortable buying online, Casper could save on costs associated with having physical stores.

Customer acquisition for the price of peanuts

In the early to mid 2010s, competition for Facebook ad slots was low, even though engagement with the social media platform was high. It was possible to reach millions of people with a few thousand dollars. Additionally, unlike traditional advertising, Facebook made it possible to precisely target audiences - by demographic, interests, or whether they had previously engaged with your content.

In 2012, the Dollar Shave Club released a deadpan monologue featuring their CEO Michael Dublin. The video went viral - it was shared widely on social media, racking up millions of views.

The company was able to capitalise on this momentum - it retargeted customers who had watched the video with personalised ads likely to result in conversion. The cost per thousand impressions (CPM) for these targeted ads was ~$5 - significantly cheaper than TV or print advertising.

With low CPMs resulting in a low customer acquisition cost, D2C companies were able to offer products more cheaply than traditional retailers, which furthered their growth and advantage.

How was their advantage eroded over time?

The copycats arrived in droves

As companies like Warby Parker, Casper, and Dollar Shave Club began to establish themselves as disruptive forces in their respective industries, other companies took notice and began to copy their approach. This led to a proliferation of D2C brands in the same category.

The emergence of copycat companies led to increased competition - for raw materials, advertising spots, and customers. As more companies entered the market, the cost of customer acquisition rose, and the advantages of being a first-mover were eroded. Ultimately, D2C companies that sold a commodity product saw their business model, product, and marketing being copied 1 for 1.

Lowered barriers to entry

To sell products in a physical store, there are barriers to surmount: you have to lease a space, decorate the shop, buy products from suppliers, manage inventory, and employ people to serve customers.

In comparison, selling products online is almost a cakewalk. Tools like Squarespace (website builder), Shopify (store builder), Stripe (payments API), and Hubspot (marketing engine) make it cheap and easy to build an online storefront, display products, and collect payments - all while delivering a seamless customer experience.

Additionally, Alibaba makes it easy to manufacture products offshore, while third-party logistics (3PL) companies make parcel delivery quick and reliable. These services erode traditional moats such as having a manufacturing capability or delivery networks.

Customer acquisition costs increase as you grow

It’s a trap that many D2C companies fall into: The first thousand customers are often easy - and cheap - to acquire. They can’t get enough of your product - they rave about it to their friends. You don’t have to nag them with retargeting campaigns - they purchase straight away. It’s tempting to draw this line up and to the right.

But not so fast.

In the vast majority of cases, customer acquisition costs (CAC) increase as companies grow. The first thousand customers are the low hanging fruit - the rest of the population doesn’t care as much or convert as quickly. What’s more, as companies expand outside their core audience, advertising costs increase in line with competition for ad slots.

It’s dangerous for companies to build their business plan around the assumption that CAC will remain the same. Businesses can go off the rails when large investments in marketing fail to deliver on projected revenue. In some cases, the more a brand grows, the more money they lose. In these scenarios, accelerating negative cashflow cycles spell the demise of the business.

What is table stakes for a successful D2C business?

AfterWork Ventures has invested in several D2C companies, from subscription pet food Lyka to tablet cleaning products Tirtyl to connected resistance trainer Vitruvian. Over the years, we’ve identified three common elements between successful D2C companies.

1. The margin from a customers’ first order > the cost of acquiring that customer

What does product-market fit look like for D2C companies? After all, there’s an infinite amount of product-market fit to be found when you give away a product for free, or significantly less than it costs you to produce and deliver that product.

In general, we believe an important litmus test is whether the real margin from a customers’ first order covers the cost of acquiring that customer.

Importantly, this is different to SaaS and other subscription-based business models, where the customer has an expected ‘lifetime value’ (CLTV). While some D2C companies are subscription-based - customers are notoriously fickle, and will churn at the drop of a hat if a cheaper or better proposition comes along. Being gross profitable on the first order gives companies the confidence to keep cranking the marketing engine - knowing they’ll only ever end up ahead.

We don’t expect all companies to have achieved this standard on Day 1 - experimentation with creative, offers, and channel will be needed. However, we believe teams should be laser focused on achieving this standard as early as possible and hold back from pouring fuel on the growth engine until it’s been achieved.

2. Inflecting growth through product differentiation and brand marketing

You’d think once you nail Step 1, you could play the ‘80c in, $1 out’ slot machine till you hit $100m in annual revenue. We’ve seen the strategy work up to $10 million in annual revenue - but eventually customers become harder and more expensive to acquire. Many companies grind to a steady-state equilibrium in the low millions of dollars of revenue.

In this rut, we’ve seen some VC-backed companies close their eyes, start setting marketing dollars on fire, and pray for a miracle: “We’ll simply subsidise growth till we reach escape velocity!! After we’re a household name, we’ll think about profitability”.

This is how companies fail. If you’re losing money for every sale you make, the faster you grow, the more money you bleed. Unlike marketplaces (and some software companies), D2C companies are rarely ‘winner takes all’: the product rarely improves for each marginal customer that is acquired. Sometimes there is no escape velocity; there is only oblivion.

Well - that’s a bit bleak. What’s the way through?

We think it’s about finding a way to inflect growth without relying on conversion-driven performance marketing, usually through focusing on product or brand. Brand is a huge topic, and warrants its own article - previously we’ve written about how Aesop perpetuated itself by building a brand synonymous with aspiration and taste, and how the best brands level up their marketing with storytelling.

Unfortunately, we see many D2C companies over-index on optimising their performance marketing engine rather than truly turning their attention to brand building: deeply thinking about segmentation, strategy, and positioning. What’s more, marketing sometimes happens at the expense of brand building - tactics like discounting and promo codes can actually undermine and jeopardise a brand’s positioning.

![Brand Archetypes: The Definitive Guide [36 Examples] Brand Archetypes: The Definitive Guide [36 Examples]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!m7nt!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F262bf3ac-8b37-4f00-81fb-2f48e19125df_1200x1200.jpeg)

3. Achieving operational excellence with scale

As discussed earlier, third party manufacturing and logistics makes it straightforward to make and sell a hundred units. In fact, businesses like Atelier are dedicated to making it straight forward to design, manufacture, and ship beauty products. But relying on third party contractors erodes margin, limits your ability to innovate on product, and leaves you exposed to copycats.

We see the best D2C companies quickly move away from third party manufacturing and in-house their manufacturing capabilities, building relationships across their supply chain, and tightly integrating R&D with product and operations. These D2C companies are able to build differentiated and proprietary products with genuine ‘secret sauce’, and realise economies of scale as they grow.

What makes a D2C company venture backable?

The three qualities above create a strong D2C business, but not all strong D2C businesses are necessarily venture backable.

Ultimately, ‘venture scale’ returns can be difficult for D2C businesses to deliver. This is partly because D2C companies are valued differently to SaaS businesses with regard to revenue multiple: SaaS companies often command 10 - 20x revenue multiples, while even high-growth D2C companies will trade at 2 - 5x revenue multiples. This is for several reasons:

SaaS companies have higher operating leverage - a larger proportion of their cost base is fixed, rather than variable. This means a large proportion of incremental revenue is incremental profit; SaaS companies can become incredibly profitable once at scale.

SaaS companies generally have recurring revenue and higher LTVs. Once CAC is paid back, revenue from a customer is incremental profit. With the exception of sticky subscription products, D2C companies have to re-engage customers for every new purchase.

It is harder to build defensibility for D2C companies; barriers to entry are generally lower, and there is less scope to create network effects.

Because of lower exit multiples, a D2C company may need to achieve 3x the annual revenue to warrant the same valuation as a SaaS company.

With all this being said, we believe three qualities put D2C companies in contention for venture backing:

1. Significant revenue potential even when under-penetrated

Because it’s structurally harder for D2C companies to dominate a market, we favour companies chasing opportunities where there is meaningful revenue potential, even when significantly under penetrated. For example, Allbirds’ 2022 revenue was $300 million - a rounding error in the $400 billion market for footwear globally.

Having a proposition that is tightly focused on a niche group within a large market can help an emergent D2C company find its group of enthusiastic early adopters, and bootstrap its way to a differentiated product and distinctive brand.

2. Defensibility

For there to be an imperative for venture funding, there must be some form of defensibility baked into the business model. We need to believe a shameless ‘fast follower’ with a spike in performance marketing can’t duplicate the business and simply win on distribution.

Manufacturing capabilities and vertical integration is one form of defensibility, as is a patentable product, as is a high-performing R&D function that is constantly driving product innovation in response to customer feedback.

Excitingly, we’ve also seen some companies invest in community as a moat - for example, D2C beauty company Glossier has a vibrant community of beauty influencers who co-create and grow alongside the brand. Creators’ user generated content is a powerful form of organic marketing for Glossier and contributes to its dynamic and relatable brand.

3. Capital efficiency

Even though venture backed companies are often initially loss-making, we believe the best ones are capital efficient. Capital efficiency refers to a company’s ability to generate value with minimal investment of financial resources - and to cover the costs of its growth with the revenue it generates.

To be capital efficient, a D2C company should be able to start generating revenue without significant upfront investment, have tight control of its cost base, and deliver quick ROI on its investments of capital. As we wrote in our investment notes on Lyka, the team optimised capital efficiency in their early days with a modular approach to scaling its factory - they negotiated a flexible lease arrangement where they only paid for factory space they used, and they iteratively built up their production capability in lockstep with customer growth.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, consumer facing companies touch everyday lives; they inspire emotion - the products we use reflect the kind of person we aspire to be.

As investors, we are excited to meet the next generation of product and brand visionaries. We hope this article helps aspiring D2C founders understand some of the pitfalls of the D2C business model, but also how to build excellence into your company. If you want to pitch your company to us for investment, get in touch!

For more from AfterWork on D2C, check out:

The Future of D2C

What I Wish I Knew Then: Lessons from 5 D2C Founders

Think DTC might be even simpler: bunch of companies invested margin that traditionally went into retailers (some 30-40%) and took 20% of the RRP price, gave 20% to the likes of Google/Facebook. Essentially it was rethinking distribution through retailers and reworking it to be price + through cheap channels.

Google/Facebook being auction ad markets meant the second those companies got competitors they would bid away their margin quickly.